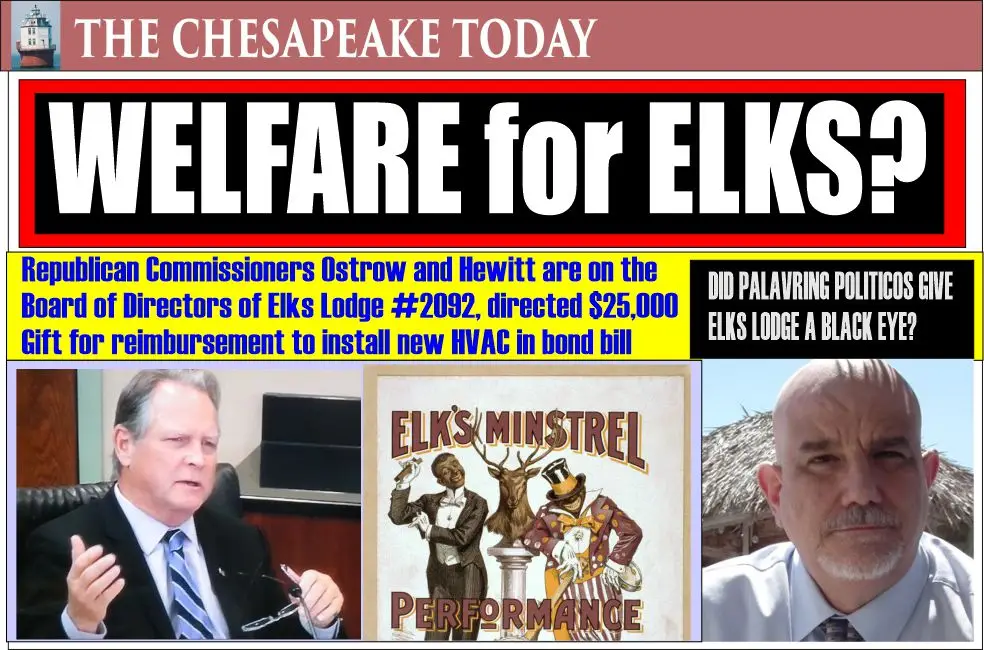

ST. MARY’S COUNTY COMMISSIONERS OSTROW AND HEWITT GUIDED THE PUBLIC BOND AUTHORIZATION OF $25,000 FOR THE ELKS CLUB’S HVAC, WHILE BOTH ELECTED OFFICIALS ARE OFFICERS IN THE LODGE

ST. MARY’S COUNTY COMMISSIONERS OSTROW AND HEWITT GUIDED THE PUBLIC BOND AUTHORIZATION OF $25,000 FOR THE ELKS CLUB’S HVAC, WHILE BOTH ELECTED OFFICIALS ARE OFFICERS IN THE LODGE

BY KEN ROSSIGNOL

THE CHESAPEAKE TODAY

LEONARDTOWN, MD – Nearly every year, a wish list of private groups, mostly claiming to do wonderful things for the community, applies for free money courtesy of the taxpayers of St. Mary’s County. The county commissioners have staff paw through the requests, shuffle them around to give some sort of air of impartiality to favoring the “correct” and “deserving” recipients. Once the list is formed, maneuvered, and manipulated through backroom questioning by individual commissioners, it is presented to the Board for approval.

Another list is shorter but can have bigger allotments of public funds and is sent to the St. Mary’s legislative delegation for inclusion in the public borrowing, known as the bond authorization, which is scrutinized by the delegation and then submitted to the General Assembly each session. Just eight years ago, the St. Mary’s County public debt, or money that can be borrowed now, spent, or designated to be spent in the capital budget, but paid back by your children and grandchildren.

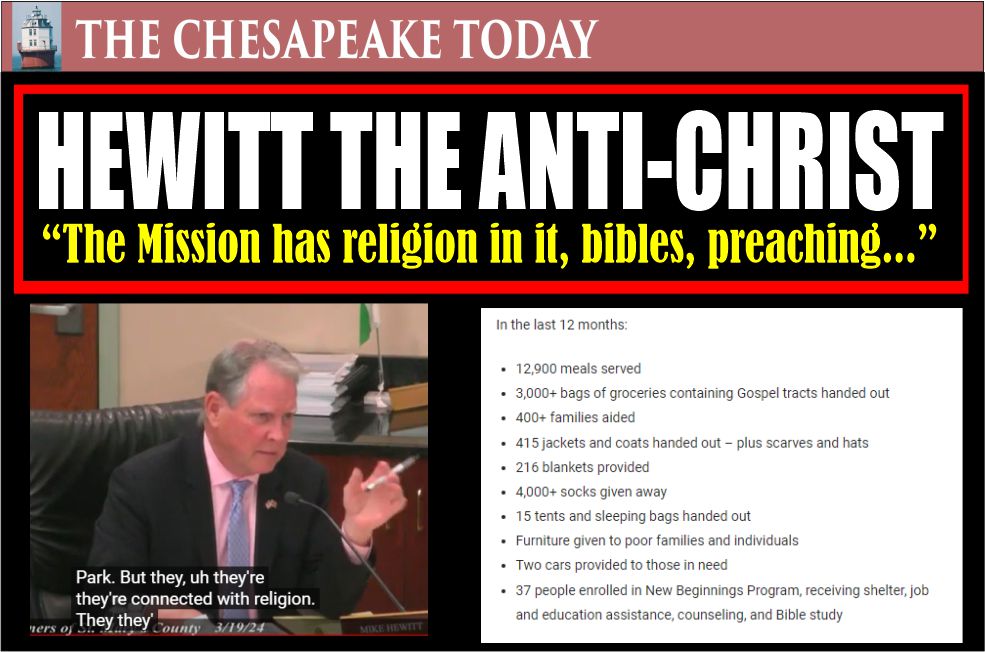

Last year, St. Mary’s County Commissioner Mike Hewitt (R. Leonardtown, Hollywood) complained about the Mission being awarded any taxpayer funds, as he said he investigated the website of The Mission and learned that the group featured “religion” in their efforts to wean alcoholics off of booze and drug addicts away from narcotics. Hewitt said he was shocked that the county staff included The Mission on the list of groups to be awarded public funds and claimed even though he himself is a “Christian”, that public funds can’t go to the Mission because it features ‘religion’.

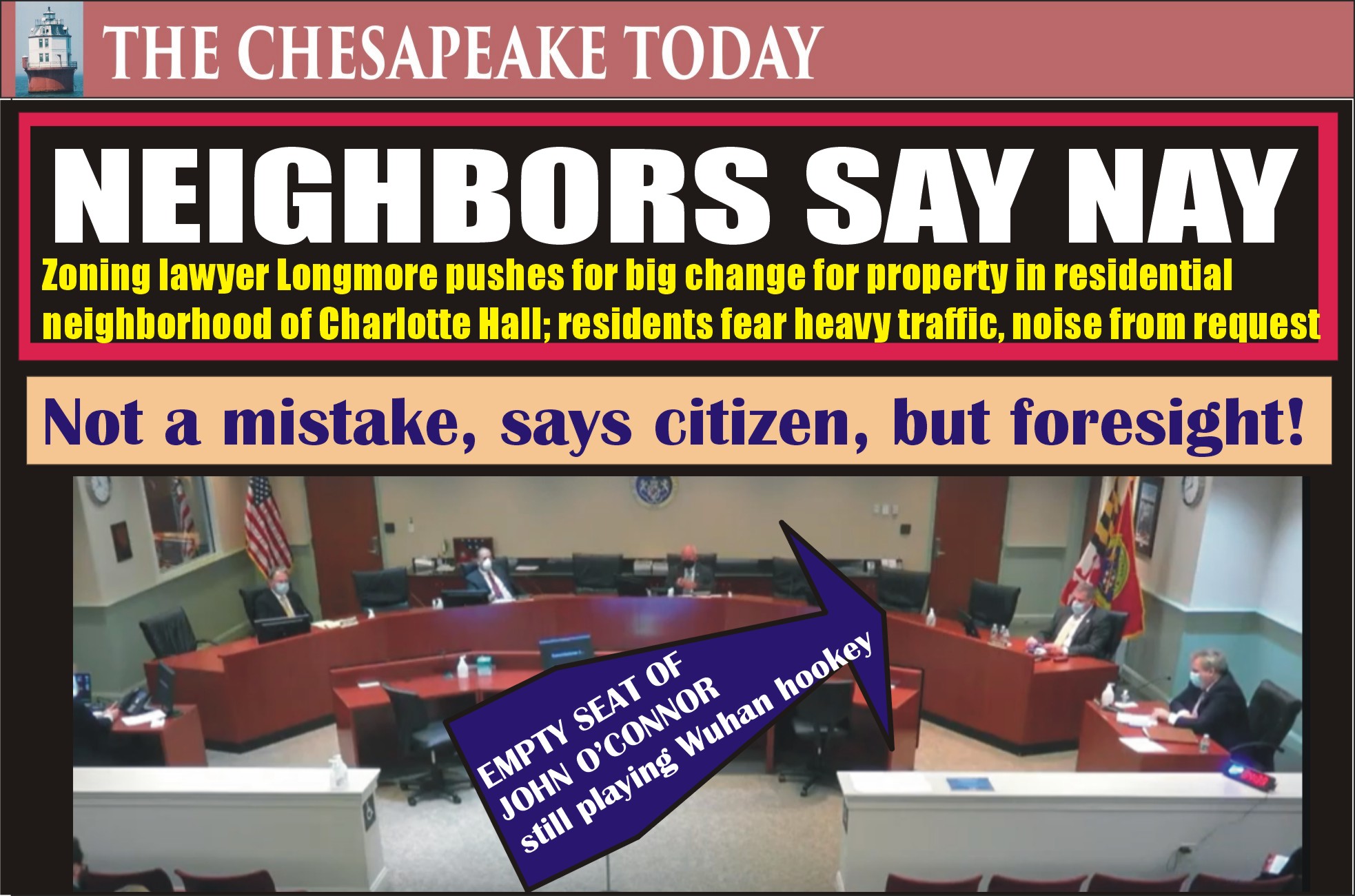

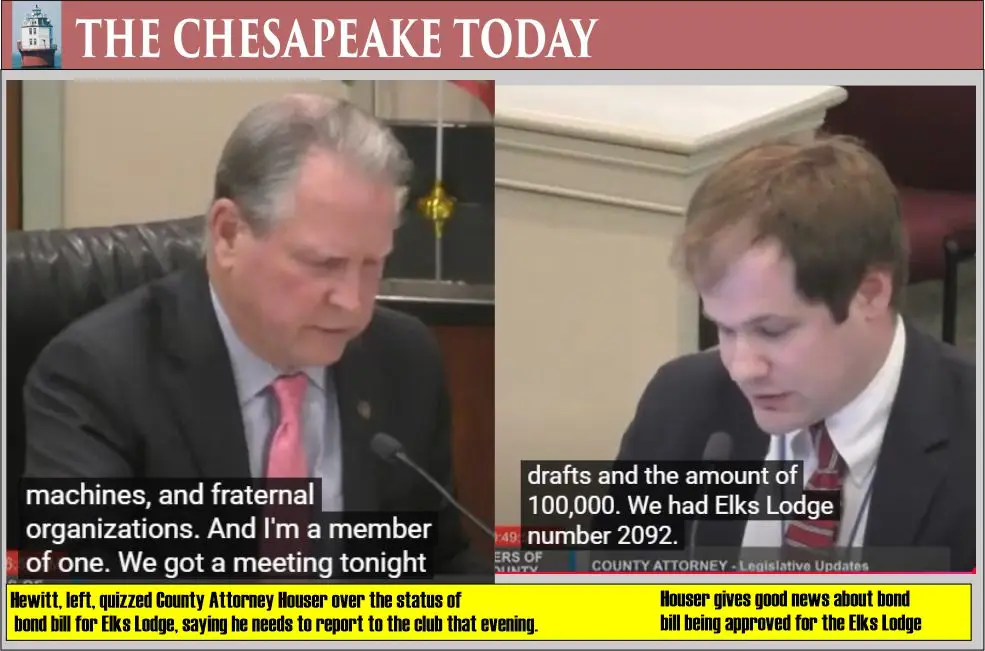

Now, in the current deliberations leading up to the recently ended General Assembly session, Hewitt carefully noted to Assistant County Attorney John Houser, during an update that Houser gave the St. Mary’s County Board of Commissioners, that he needed to know the status of a bond approval for a fraternal organization of which he is a member, as the club had a meeting that night. He wanted to report to them about a bond authorization that was pending approval. The bond authorization was for $25,000 to reimburse Elks Lodge 2092, located in California, Maryland, for the replacement of their HVAC system.

The bond will be repaid by taxpayers, not through any special tax assessment by the Elks.

The Elks will not be opening their private pool to the public in consideration of the taxpayers’ gift to them of the reimbursement of the cost of cooling and heating their banquet facility.

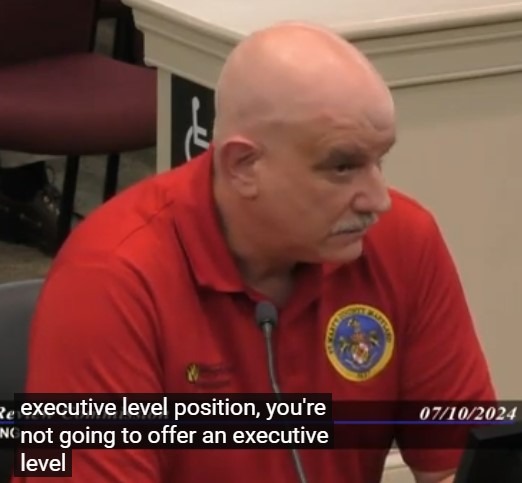

Both Hewitt and Commissioner Scott Ostrow (R. Lexington Park) are officers of the Benevolent Order of the Elks Lodge #2092.

The Elks are a private club, and membership is only available after being sponsored by a member in good standing with two members as references, with an investigation then undertaken, and finally a vote of the membership. The four requirements are as follows:

To be eligible for membership, you must:

- Be at least 21 years of age.

- Believe in God.

- Be a citizen of the United States who pledges allegiance to and salutes the American Flag.

- Be of good character.

Ironically, Commissioner Hewitt sees nothing wrong with his condemnation in 2024 of The Mission having religion in it’s beliefs in assisting the downtrodden fix their error of their ways and obtain sobriety and redemption with a boost of religion to help make the medicine go down; and his willingness in 2025 to have public funds go to his private club, based on belief in God, to reimburse the organization for the cost of a new heating and air-conditioning system.

Hewitt’s head must be spinning like Linda Blair in the role of Regan in the movie ‘The Exorcist’ as he revolves around doling out money, figuring out religion, and sorting out demons. Ostrow moves around pretty well for a novice commissioner, finding himself a place on the Elks Officers’ board as he sprints to the next election and votes by Zoom to raise taxes from his Alaska cruise ship.

ELKS LODGE ON PUBLIC WELFARE

The Facebook page for the Elks Lodge #2092 indicates that there are more than 500 people as members, and given that the club had already paid for their new HVAC, perhaps the reimbursement came not from necessity but from the desire of the two St. Mary’s Commissioners to ingratiate themselves with their club the year before the next election in which both are expected to be candidates. Ostrow is already raising money for the 2026 commissioner race, and Hewitt is expected to challenge Delegate Matt Morgan (R, District 29A).

The Elks Lodge in St. Mary’s County had a policy of excluding blacks from membership, prompting a group of black citizens to form a local chapter in Valley Lee of the Improved Benevolent Order of Elks.

The Benevolent Order of the Elks, in Maryland and nationally, through its racial exclusion policies, which specified that only whites could belong, ran afoul of public accommodations laws regarding issuing liquor licenses to organizations that refused service based on race. The Elks Lodge in St. Mary’s County had a policy of excluding blacks from membership, prompting a group of black citizens to form a local chapter in Valley Lee of the Improved Benevolent Order of Elks. Until recently, although the Elks sponsored youth activities through fundraising, black children were not allowed to swim in the Elks Lodge swimming pool.

The various department heads of the county government work closely with the Board of Commissioners and provide detailed presentations on the activities of their departments, including the Economic Development Director. Under the supervision of the Economic Development Director, Chris Kaselemis, the tourism section promotes local businesses with its Visit St. Mary’s website.

Until recently, although the Elks sponsored youth activities through fundraising, black children were not allowed to swim in the Elks Lodge swimming pool.

The Visit St. Mary’s website, under ‘Events,’ lists the Elks Lodge #2092 for banquets but fails to include a black-owned camping, fishing, and banquet facility, Seaside View, located in St. Inigoes. Seaside View operated under the gentle guidance of Vincent Biscoe for decades until his death in 2017, and now continues in business under the care of family members.

Another locally minority-owned venue not included on the St. Mary’s website is Water View Inn at Bushwood, formerly Brambly Inn, operated by Viola Gardner and then the Carter family, now is operated by Dwayne Thomas and David Thomas.

Seventeen banquet hall rentals are featured on the St. Mary’s County tourism website, including the Elks, the county-owned country club at Wicomico Shores, Christ Episcopal Church at Chaptico, the Hollywood and Bay District Firehouses, the American Legion hall at Avenue, Sotterley Plantation, Potomac Gardens at Colton’s Point, Sutler Post Farm, Taphouse 1637, White Rose at Callaway, The Southern Maryland Autonomous Research and Technology (SMART) Building at the county airport, are among the venues featured for free on the Visit St. Mary’s website.

While the county-owned Wicomico Shores golf club and the firehouses are taxpayer-supported, the SMART building is a public facility. The others are privately owned and members-supported facilities. None of them have obtained special public bond infusions of cash or have county commissioners on their boards, such as Elks Lodge #2092. While historic Sotterley was an actual plantation and held slaves against their will until the Civil War, only the Elks Lodge has a history of excluding blacks.

HISTORY of Discrimination in The Elks

100 Years of Elks Discrimination in Annapolis

FROM THE BALTIMORE SUN

BALTIMORE- May 19, 2003 – Citing a local Elks Club’s century-long record of discrimination against African Americans, the American Civil Liberties Union of Maryland and a local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People today urged the Anne Arundel County Fire Department not to hold a county-sponsored banquet at the facility this Thursday.

“The Elks Club is a public accommodation that still is not complying with civil rights laws that have been on the books for nearly four decades,” said Susan Goering, Executive Director of the ACLU of Maryland. “We call on the Anne Arundel County Executive and County Council to promulgate a policy that forbids spending taxpayers’ money in any facility that still discriminates in 2003.”

According to ACLU attorneys, the Annapolis Elks Lodge #622, which boasts over 1,500 members, celebrates its 100th birthday this year, but has still never had an African American member. Under Elks bylaws, in order to become a member of the lodge, a current member in good standing must recommend an applicant.

Throughout its history, charges of discrimination have plagued the lodge. Thirty years ago, the lodge came under fire from the Department of Justice when it refused to allow an 8-year-old African American boy to play on a lodge-sponsored Little League football team. Critics charged that the discrimination was unacceptable when civic associations like the Elks Club reap hefty state and federal tax benefits on the theory that their benevolence programs — like the Little League teams — provide value to the community at large.

In 1990, Lodge #622’s membership policies again came under scrutiny after Annapolis passed an ordinance that required private clubs to stop discriminating on the basis of race and gender in order to receive liquor licenses. While other private clubs in Annapolis changed their policies and began accepting women and African Americans, Lodge #622 chose instead to challenge the ordinance in court.

When the Maryland Court of Appeals ultimately ruled against the lodge, it moved its facilities out of the city and into Anne Arundel County. The ruling was a landmark decision, making Annapolis the only municipality in the state to prohibit alcoholic beverage licenses to clubs that discriminate. Lodge #622 has since admitted women to membership, and the current Exalted Ruler is a woman, but African Americans have never been admitted.

Last December, the Maryland Housing Community Development Agency, a government agency, decided not to hold its holiday party at the Elks Lodge in light of the lodge’s long policy of exclusion based on race.

“In a city that is now one-third African American, it is high time for this last vestige of discrimination in Annapolis to fall,” said Gerald Stansbury, President of Anne Arundel’s NAACP Branch. “It is patently unfair to ask African American firefighters and their family and friends who want to attend this work-related event to go to a place that otherwise would not want them walking through the door.”

In the late 1980’s, following a series of Supreme Court opinions that sanctioned local civil rights laws forbidding discrimination in private clubs, the ACLU and other civil rights organizations founded The Coalition for Open Doors. An ACLU lawsuit against the 6,000-member Hagerstown Moose Lodge, which ran a public accommodation that discriminated, forced the club to close its doors in the mid-1990s.

LESSONS ON RACISM:

THE SENIOR PROM AT THE ELKS CLUB

By Donna M. Hughes

Dignity: A Journal of Analysis of Exploitation and Violence

THIS ESSAY EXPLORES LASTING LESSONS on racism. I describe my observations on how shallow but deeply stubborn racism continues to be.

I attended my 50th-year high school class reunion. I graduated from the State College Area High School in Pennsylvania in 1972. As I look back and think about my experiences, one controversy has stuck with me for decades: The debate on where to hold the senior prom. The arguments and outcome turned into a lesson on the practice of racism. And I am still learning after 50 years.

The senior prom was held at the local Elks Country Club for years. In 1972, the Elks’ whites-only membership policy became a sticking point. The town of State College in rural central Pennsylvania was overwhelmingly white, with only a tiny black population. There were only three or four black students in our class of about 550. In this time of growing awareness of racism, some students said the class should find another venue because the Elks had an exclusionary, whites-only racial policy. However, many students wanted to go to the Elks because it was arguably the nicest venue in town to accommodate the numbers attending the prom. A debate ensued.

There were other debates like this breaking out around the United States. In Deering, Maine, in 1971, Una Richardson, one of only two black students in a class of 427, spoke out against holding the senior prom at the Elks Club, which had a whites-only membership. She said it was wrong for the class to hold a prom where her father couldn’t be a member. The class voted to keep their prom at the Elks Club (Bouchard, 2013).

At State High, a class assembly was held to discuss the decision. The pro-Elks contingent had their arguments well-rehearsed. They said: “The Elks membership policy will not apply to the prom;” “It’s the best place in town;” “We want a nice place for the most important event before graduation;” and anyway, “The Elks is going to change their policy soon.” Then, a tall, handsome, athletic black man stood up and began to talk. Bruce Ellis was a star athlete and one of the few black students in the class. He clearly said that the prom should not be held at the Elks Club because of their whites-only membership policy, and he personally felt, as a black student, he could not attend an important event of his senior year if it were held in a place where he and members of his family could not be members. He could not have been clearer with his message against racial discrimination.

Later, it was announced that the prom would be held at the Elks Club.

My young, naïve idealism was cracked. Growing up during these times, I absorbed the equal rights ethos of the civil rights movement. I became idealistic and assumed that a new social consciousness was all that was needed to end discrimination. I mistakenly assumed that racism was a matter of ignorance, that people just hadn’t thought about their attitudes and actions and the implications for others.

The young man, Bruce Ellis, became a football wide receiver for Penn State University. He worked for Penn State as an academic advisor and the Director of Undergraduate Programs at the Smeal College of Business and later as the Assistant Athletic Director of Student-Athlete Services (Miller, 2009). I went on to get my Ph.D. and become an academic. I researched sex trafficking and advocated for new laws and policies to protect victims and hold perpetrators accountable.

Fifty years later, I spotted Bruce at the high school reunion and decided to talk to him. I told him I remembered that day he stood alone and spoke out against discrimination and the proposal to hold the senior prom at the Elks Club. At one point, Bruce said, “Who made the final decision?” I said there hadn’t been a class referendum, so it must have been the class president(s). That year, instead of electing a class president, a triumvirate of three male students ran to be the president(s)—Derf Hensel, Dave Laughlin, and Martin Ford. As it turned out, Derf was standing just 10 feet away from our conversation. I called Derf over and said, “We were just talking about the controversy over the senior prom being held at the Elks Club.” He jumped up, shook his head, and started to leave, saying he didn’t want to talk about it. Then, he quickly turned back to me and asked, “Who made the decision?” I looked curiously at him and said, “I assumed it was the class presidents. You were the class president.” He patted me on my shoulder and said, “I’m not going to talk about it.” He quickly walked away again, returning to his conversation. Bruce and I looked at each other with some disbelief. Bruce said, “When people show you who they are, believe them.”

I was shocked that a professional man in his mid-60s refused to discuss a school prom controversy. I thought he would pause and say something like, “Upon reflection, we should have made a different decision.” I decided to write something about this controversy and my 50-year education on the depths of stubborn racism in our high school.

First, I needed to do a little research on the Elks Club for background. Over my 40 years of researching sexism and racism, there has been a common theme: When I hear that something is bad, I find that it is always worse upon investigation. And so, it was with the Elks Club.

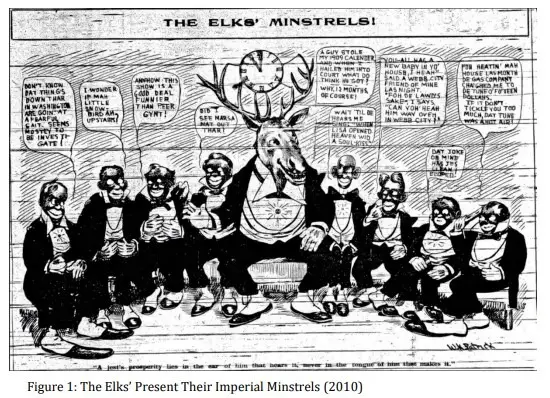

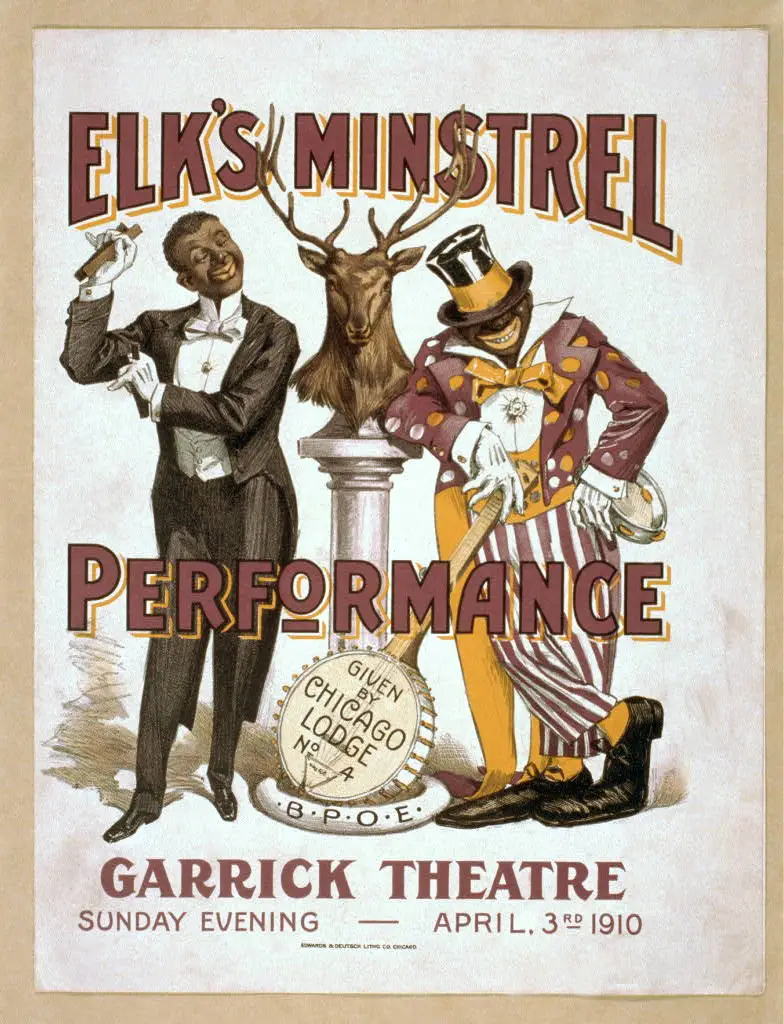

The Elks Club was formed in 1868 as a social club for minstrel show performers.

The black-face performers portrayed blacks as buffoonish, illiterate, superstitious, lazy, and often yearning for life on the old plantation.

Minstrel shows were comedy, musical, and theatrical entertainment performed by white men who blackened their faces and sang, spoke, and acted as racist caricatures of black people. The black-face performers portrayed blacks as buffoonish, illiterate, superstitious, lazy, and often yearning for life on the old plantation.

Although the Lions Club and the Rotary sponsored and raised funds from blackface minstrel shows, the largest single organization behind the promotion of blackface was the Elks Club; by the mid-20th century, the Elks Club was the largest fraternal group in the United States. The Elks and their shows were popular among U.S. presidents, legislators, and military leaders (Barnes, 2019).

The Elks Club was a leader in promoting white supremacy through racist entertainment. This information prompted me to search my memories for what I personally know about minstrel shows.

I recalled a memory from 1964 or 1965. I remember seeing a minstrel show performed by the 6th-grade class at the Matternville Elementary School in rural central Pennsylvania. I didn’t understand it then, and only now do I recognize it for what it was. The student performers were dressed in ill-fitting, tattered clothes and had what looked like dirt rubbed on their faces. I didn’t get it. I did not understand why they were dressed like that and looked dirty. They sang the songs we were taught in music class, such as “Oh! Susanna,” “Camptown Races,” “Blue Tail Fly” / “Jimmie Crack Corn” (n.d.),” “Old Folks at Home,” and “I’ve Been Working on the Railroad.” I still remember those songs and most of the lyrics. I now realize we were taught the stock songs of the 20th-century minstrel show in elementary school music class.

My further research found that minstrel performances were common in schools (Black-face minstrel show mars, 2019). As part of the civil rights movement, Black women organized campaigns and filed legal cases to ban black-face performances, dress-ups, and texts from schools (Barnes, 2019). After complaints from the Pennsylvania chapter of the National Association Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the Pennsylvania Department of Public Instruction recommended that all public schools end performances of black-face minstrel shows.

The year after I graduated, in 1973, the Elks Club voted to remove “white” from the requirements for membership. This action followed a court ruling that a liquor license could be withheld from an organization if it discriminated against nonwhites in its membership requirements (White-only rule dropped, 1973).

As a result of this end to public school black-face minstrel shows, I missed my opportunity to participate in a minstrel show. When I was in 6th grade, the teacher, Lois Bailey, who organized the show each year, announced with some disgust that we were no longer allowed to have the “traditional” show. While researching this topic, I learned that Mrs. Bailey was still alive. She was 93 years old. I contacted her. She remembered me. I asked her if she remembered anything about the minstrel shows at Matternville School. She didn’t want to talk about it either and never replied. (She died early in 2003.)

Looking back, I wonder if I, at age 12, would have figured out what the minstrel show was about. Of course, no one said the obvious out loud. Still, there continues to be silence, even when it seems to me that a simple, honest conversation would solve so much.

Bruce Ellis concluded our conversation at the reunion by saying, “Now you know why we are still talking about [race].” Hughes, Donna M. (2024). Lessons of racism: The senior prom at the Elks Club. Dignity: A Journal of Analysis of Exploitation and Violence. Vol. 9, Issue 1, Article 5. Available at http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/dignity/vol9/iss1/5.

Discover more from THE CHESAPEAKE TODAY - ALL CRIME, ALL THE TIME

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.