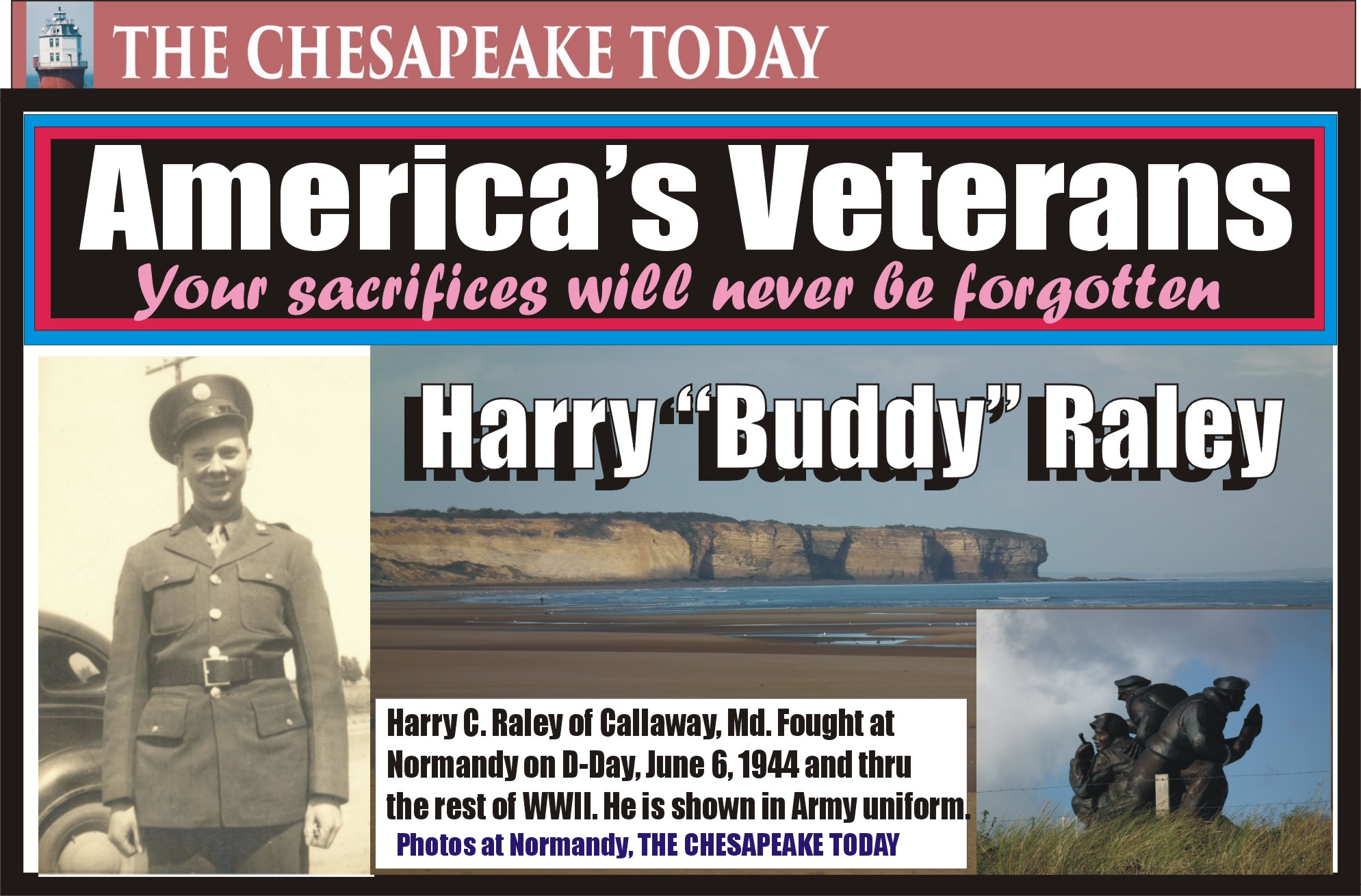

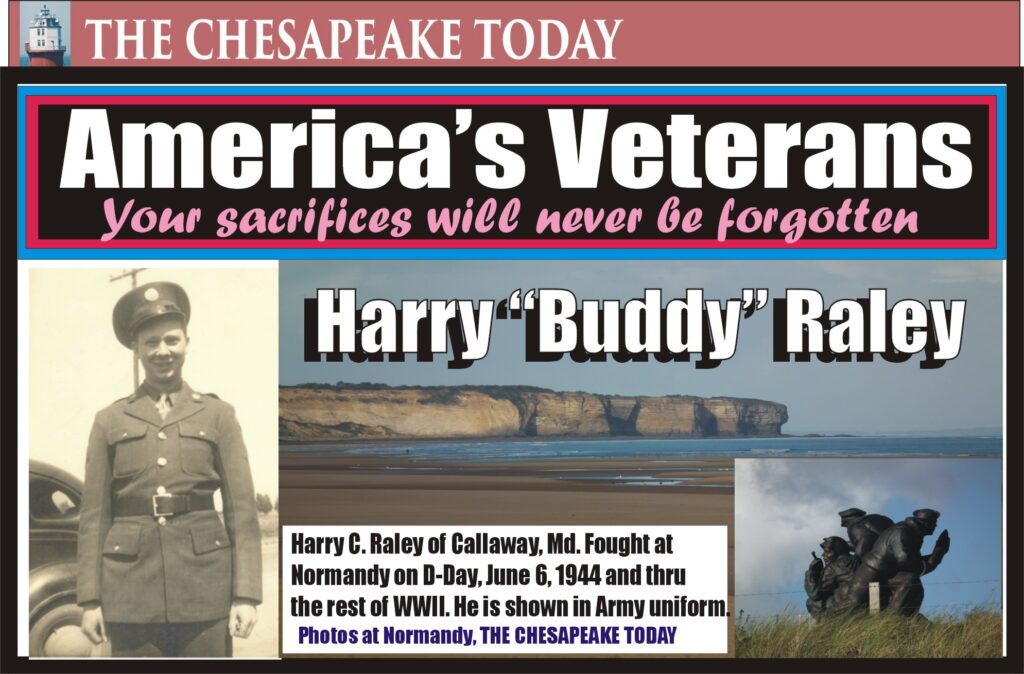

Harry “Buddy” Raley in 1942, just after being drafted into the United States Army.

World War II Heroes: ‘ Your Sacrifices Will Never Be Forgotten’

THE CHESAPEAKE TODAY SPECIAL FEATURE

(Editor’s Note: This article was initially published in 2006 and is being presented again as a tribute to America’s Veterans in 2021.”

CALLAWAY—Sixty years ago, Harry “Buddy” Raley realized first-hand the brutal, murderous actions taken by Adolf Hitler’s Nazi regime when he walked through the Nordhausen concentration camp

“It was the most horrible thing I’ve ever seen; the smell was so bad you had to wear your gas masks, and guys were vomiting,” Raley said. “The smell of human bodies is like awful, like nothing else.”

While some people may not realize the magnitude of actions taken by men like Raley to literally save the world from evil, the images of World War II are embedded in his mind with crystal clarity.

“Some of it is as clear as the day it happened,” said Raley, 81, during an interview in his Callaway home. “I remember landing on that beach like it was yesterday, and I was 20.”

On June 6, 1944, Raley landed on the beach in Normandy, France, along with more than a million American and allied troops, to begin a sweep across Europe that marked the beginning of the end of Hitler’s reign.

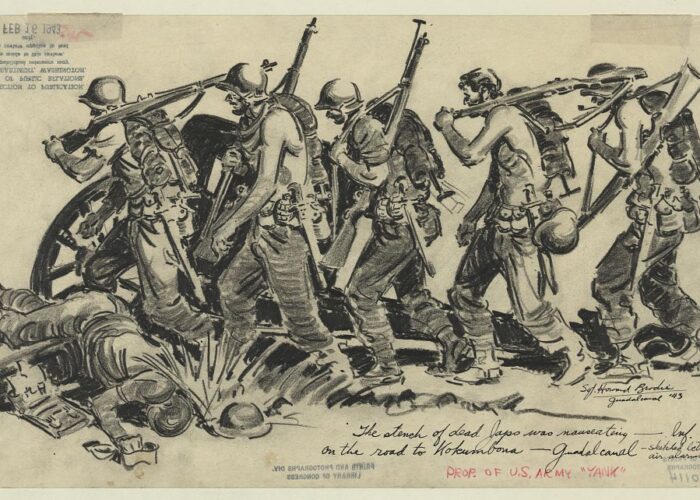

He was a member of the 1st Army, VII Corps Antiaircraft Artillery 474th division. Raley’s division drove “half-tracks” directly on Utah Beach from “landing craft tanks.” They landed two hours after thousands of infantrymen stormed the beach on foot, as portrayed in the movie “Saving Private Ryan.”

“It’s one of the worst jobs in the world to have to pick up your buddies in pieces,” Raley said Thursday, unable to hold back the tears in his eyes. “… and they were just up walking around a little while ago.”

He saw much death, and his unit is credited with taking out more than a hundred German fighter planes. He is proud of the Allies’ victory over Germany, but many memories are hard to recall without tears, even the good times.

Raley’s division was dubbed the Maverick Outfit. The half-tracks were a cross between a truck and a tank, with tank tracks in the rear. The antiaircraft guns on the half-tracks were designed to shoot down enemy jets, but they also did the job on enemy tanks.

“Wherever they needed us, we would go; that’s why they called us the Mavericks,” he said.

Raley grew up in Callaway, two houses down from where Raley’s Alignment is today.

At 18, he was drafted into the Army on Dec. 12, 1942. After tactical training at bases in Maryland, Massachusetts, Kentucky, Tennessee, and North Carolina, “crawling under barbed wire,” he boarded a ship in New York headed for England on about Jan. 1, 1944.

“I’ve been a very lucky man, and a lot of guys weren’t so,” he said. “A lot of guys didn’t make it on that beach.”

After he drove on the beach, the antiaircraft units had to wait several hours while combat engineers destroyed a concrete wall in the way of the tanks and half-tracks.

The Allies secured the seaport town of Cherbourg, and Raley’s men easily captured sixteen surrendering German soldiers.

To Mortain, across France toward Belgium, the “triple-A” antiaircraft artillery unit traveled, supporting advancing infantry. Sometimes, the triple-A units moved ahead of the advancing front lines.

He recalled one occasion British warplanes dove down toward his unit’s position and opened fire, mistaking the VII Corps for the enemy. No one was hurt, and the planes pulled back after the men laid out the bright orange markers that signified they were allies.

During his year over there, Raley was not injured, but he had many close calls. He remembered a time driving a truck back to where the men were camped, and German’s were dropping artillery shells on the road behind him.

“Boy, did I hit the gas then,” he said. “They got pretty close to me a couple of times, a little too close for comfort.”

Another time, his unit came upon a German troop train heading to the Battle of the Bulge. They turned their antiaircraft guns on the train and blasted the engine car, sending German troops running in all directions.

“It was quite an ordeal, I tell ya.”

“Once we captured a town, and the older Germans there were very pleasant, they were glad we were there,” Raley said. “But before that, they couldn’t tell us because Hitler would have them executed.”

“I still get shook up about it all,” he said.

With all the horrible scenes of war, Raley wishes no one would have to see combat. “No one likes killing people, but it’s shoot or be shot, you know.”

In one confusing emotion, the war was the greatest and worst time of his life.

“But I wouldn’t trade it for any experience in the world,” he said. “It made a better person out of me.”

Thursday marked Buddy’s and his wife Thelma’s sixtieth wedding anniversary. Occasionally, when he is out wearing his “World War II Veteran” hat, people stop him in the street and thank him for winning the war.

And he appreciates that.

Raley lost close friends in the war. And he watches as other WWII veterans die every day.

“It’s later than you think sometimes.”

(Harry Calvin Raley, 88, died surrounded by his loving family at his residence in Leonardtown on Monday, June 18, 2012.)

Discover more from THE CHESAPEAKE TODAY - ALL CRIME, ALL THE TIME

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.