By KEN ROSSIGNOL

THE CHESAPEAKE TODAY

LEXINGTON PARK, MD. –

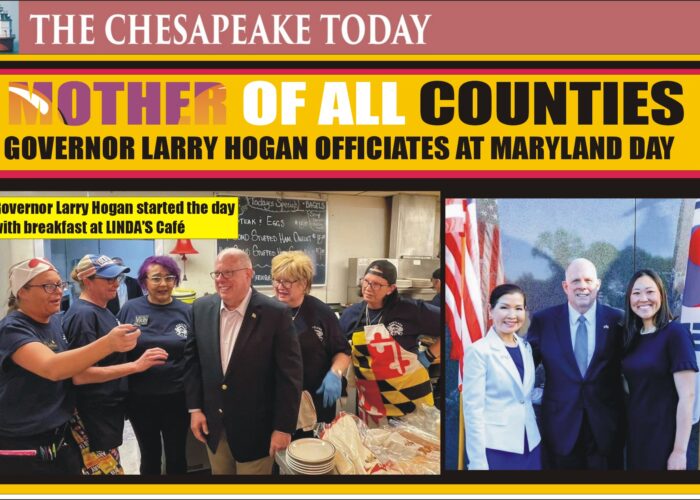

Maryland Governor Larry Hogan was in St. Mary’s County for the 388th anniversary of the founding of Maryland on March 25th and 26th, spending the night in the county and doing what so many others do on a Saturday by having breakfast at Linda’s Café in Lexington Park.

Governor Hogan toured Leonardtown on Friday, March 25th after a visit at the St. Clements Island Museum at Colton’s Point for the 388th anniversary of the landing of the colonists in Maryland after a three-month journey from the Isle of Wight in England. In past years more sturdy officials ventured out on vessels to St. Clements Island for the celebration of Maryland Day and also in the summer for the Blessing of the Fleet.

The Maryland Governor and his family decided to start the day on Saturday, March 26th with breakfast at Linda’s.

“Governor and Mrs. Hogan ordered the Southern Maryland Stuffed Ham omelet, said owner Linda Palchinsky. “They ate and then Governor Hogan went from table to table greeting people and visited. Lots of people told me he should run for President, he’s very personable.”

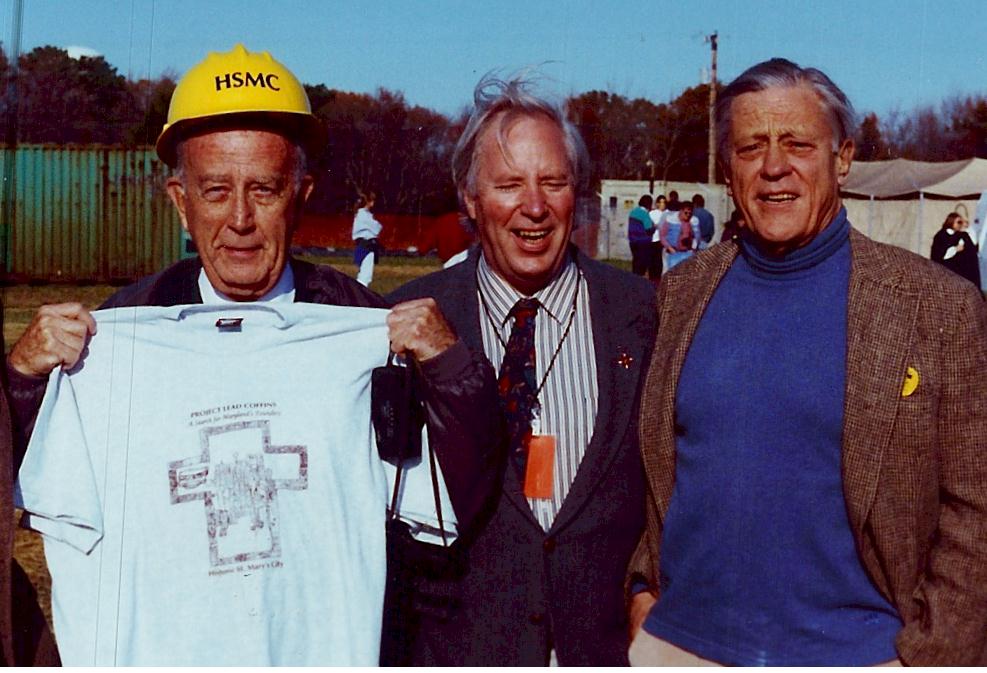

Since 1973 I have witnessed Maryland Governor Marvin Mandel, Acting Governor Blair Lee III, Governor Harry Hughes, Governor William Donald Schaefer, Governor Paris $Pendening, Governor Robert Ehrlich, Governor Martin O’Malley and now Gov. Larry Hogan all come to St. Mary’s County and most of them to St. Mary’s City at one time or another for various reasons. They all sit on stages, gave speeches, mingled with crowds, and administered important distinctions to dignitaries such as the Order of Cross Botany to inspire future generations to discover Maryland history.

The visit of Governor Hogan going to Linda’s Café for breakfast and posing for photos with four middle-income wage earners and a small businesswoman is a lot more instructive about where he stands than hobnobbing with the elite of St. Mary’s City. From the photo, it can be discerned that the Linda’s crew liked the visit.

Hogan then went to a Cherry Blossom Festival in the park created on the land that once was the site of the FLAT TOPS, the first Navy housing built during WWII to provide homes for the servicemen and their families that were assigned to and built the Patuxent River Naval Air Station in 1943.

From there the Governor went to greet legislators and others at the rebuilt Colonial State House at St. Mary’s City, which included some legislators that may be rethinking their decision to avoid wholeheartedly supporting Governor Hogan’s daughter Jaymi Sterling’s bid to be elected States Attorney in the GOP Primary election.

Politics is a cutthroat business in that one elected official won his race in 2018 only due to the intercession by Governor Hogan but now is failing to rally for Sterling’s campaign to be the first woman elected to the post of States Attorney in the nearly four-hundred-year history of St. Mary’s County.

Rebellious politics is nothing new in St. Mary’s County as an army was raised in the Seventh District and Calvert County in the 1600s and marched on St. Mary’s City to rid the state of Catholic control.

Conspiracies and Rebellions in Maryland, 1650-1681

The Maryland Disease:

Popish Plots and Imperial Politics in the Seventeeth

Century

The colony that the Calverts built in Maryland reflected George Calvert’s desires – though it was George’s son Cecil who actually made good on his father’s plans. The first Maryland colonists went to a colony that dealt with the problem of religion by essentially ignoring it. The colony intentionally chose not to provide for any kind of religious establishment, and in the famous “Act Concerning Toleration” in 1649 set out a broad program of freedom of religion. These laws led to the creation of a remarkable colony with a fair amount of diversity: there were some Catholics, though

not much more than 10% of the population, but far more dissenting Protestants. Quakers came in large numbers, as did Puritans who fled the less friendly rule of Sir William Berkeley in Virginia.

At the same time that they set up a society that allowed a high degree of religious freedom, the Calverts also set up alliances with local Indians, including the Piscataways and Patuxents. Indeed, by the admittedly low standards of the time, Maryland’s proprietary government had a good

record with the natives. Aside from the leaders themselves, Jesuit priests set up missions in the backcountry. This worried even other Catholics. Indeed, when Cecil Calvert had a theological fight with the Jesuits during the late-1630s, he worried that they might use the Indians as a fighting force

to force the proprietary leaders to do their bidding. As time went on, these fears would become even more widespread.

On its face, early Maryland looks if not like a utopia, at least like a functional and forward-looking polity, one that managed to avoid both the religious persecution common in New England and the terrible racial violence of Virginia. But most people who lived in the colony, especially the

large numbers of radical Protestants, failed to see things so positively. This combination of factors – Catholic rule, religious toleration, good relations with Indians – seemed to suggest only one thing: a conspiracy was afoot. Over the next few decades conspiratorial fears became increasingly

widespread, and the colony’s peculiar version of antipopery – one that combined fears of Catholics and Indians –turned Maryland into one of English America’s most unstable polities.

The troubles started early, in the 1650s. In the wake of England’s civil war, which had ended with the execution of King Charles I, who many had feared to be a secret papist Protestants in Maryland feared that the proprietor and his allies were attempting to undermine Protestantism.

It seemed unwise to allow a Catholic to remain in power during such times. More than that, Marylanders came to think that Lord Baltimore aimed to create a “receptacle for Papists, and Priests, and Jesuits,” and he intended to bring in 2000 Irish settlers who “would not leave a Bible in Maryland,” very alarming as in 1641 Irish Catholics had risen up against Protestant rule. According to another anti-proprietary activist, Baltimore had added Indians to his list of shadowy allies.

In 1655 the proprietor’s men had faced off against rebels at the Battle of the Severn, and according to the author, “the Indians were resolved in themselves, or set on by the popish faction, or rather both together to fall upon us: as indeed after the fight they did, besetting houses, killing one man, and taking another prisoner.”

At this point, the connection between evil Catholic masterminds and vicious Indian subordinates was far from certain, but from 1655 on it became a standard line of Maryland Protestants as they protested the proprietor’s rule. In 1676, for instance, in the wake of Bacon’s

Rebellion in neighboring Virginia, Protestants in Maryland lodged yet another complaint against the proprietor’s rule, which by this time had changed hands to Charles Calvert, the third Lord Baltimore.

The petition, delivered by agents to the Committee on Trade and Plantations in London, claimed: “the platt form is, Pope Jesuit, determined to over terne England with fever, sword, and distractions within themselves, and by the Maryland Papists, to drive us Protestants to purgatory, with the help of French spirits from Canada.”

In addition, the petitioners claimed that Lord Baltimore had encouraged the recent Susquehanna attacks on Maryland and Virginia.

All of these complaints demonstrated the degree to which antipopery inflected Maryland politics.

Having Catholics rule over Protestants was bad enough, but beyond that, the Calverts tended to adopt a style of rule that bypassed the lower house of the legislature and therefore corresponded to Protestant beliefs that popery and the arbitrary government went hand in hand.

But what is interesting is how this variety of antipopery differed from its English equivalent.

Marylanders quickly racialized antipopery; they added Indians to the popish plot, and this made it more worrisome. The next example of this occurred in 1681, and it nearly brought down the proprietorship.

During the summer of 1681, some murders occurred on the upper reaches of the Patuxent and Potomac Rivers. It was a tense time; fears of a popish plot raged in England itself, which had become inflamed over whether or not the heir to the throne, the Catholic duke of York, should be allowed to become king.

Thus when the killings occurred, it was perhaps not surprising that some colonists began whispering “that it is the Senaco Indians” who had committed the murders “by the Instigation of the Jesuits in Canada and the Procurement of the Lord Baltimore to cut off most of the Protestants of Maryland.”

The players in the plot were interesting. There was the proprietor, of course, French Jesuits, who were quickly turning into the primary villains in all of North America, and the “Senacos.” This was a fictional Indian nation. There was a real, the westernmost Iroquois tribe in New York, but Marylanders tended to call any strange Indians Senecas. It was a name that conjured

up great fear, and little information.

Depositions help us to reconstruct how these rumors started. They probably began with a man named Daniel Mathena. When the murders occurred, Mathena remembered that several years earlier he had entertained an Indian who carried several letters that he carried to the Seneca Indians from Lord Baltimore. Mathena asked how the Indians could read the letters, and the messenger replied, “that the French were hard by and could read the letters.” With the benefit of hindsight, Mathena realized that these letters must have been orders from Baltimore “to come and cut off the Protestants.”

He told his neighbor, a former governor and enemy of the proprietor named Josias Fendall, who passed the word his friend John Coode, a member of the lower house and militia captain in Calvert County.

Soon they were on a mission to bring down Lord Baltimore.

Coode and Fendall acted out of a genuine fear. They also acted for self-interest. Fendall wanted to be elected to the assembly, and thought that acting against the Catholic-Indian plot would make him more electable. Coode seems to have been a little insane. But the fact that these two men managed to gain such a following shows how much purchase such fears had in Maryland at this time. The two men even traveled to Virginia, where they tried to convince that colony’s secretary that he was

in danger as well. They breathlessly related “that the Papists and Indians were joined together.”

The secretary downplayed these fears, at which point Coode exploded and swore “God damn all the Catholick Papist Doggs” and resolved to “be revenged of them, and spend the best blood in his body.”

Baltimore attempted to solve the crisis by going after the men who spread the rumors.

He arrested Fendall and Coode, comparing them directly to Nathaniel Bacon, the rebel who had burned down Jamestown five years earlier. This approach backfired because the men were quite popular. The lower house refused to even dismiss Coode, and a Charles County justice of the peace engineered an unsuccessful bid to break the two men out of prison. Eventually, Fendall was

convicted and banished to Virginia, but Coode was acquitted and remained in a position of power.

Put simply, Maryland politics in the 1680s was inherently unstable, and this instability rested on a very specific kind of paranoia. Anytime there was a disturbance involving Indians, or even rumors of trouble, suspicion immediately fell on Lord Baltimore. He tried to expose his accusers as liars and frauds, but with little success. As Virginia’s governor wrote just after the crisis, “Maryland is now in ferment, and not only troubled with our disease, poverty but in very great danger of falling into pieces whether it be that the old Lord Baltimore’s political maxims are not pursued or followed by

the son, or that they will not do in this age.”

By the old Lord Baltimore’s political maxims, the writer Thomas Culpeper could have meant a number of things, but foremost among them was the belief in toleration. Was this a utopian vision that “will not do in this age”? Culpeper thought so, and events bore him out.

As these rumors spread, first to neighboring counties in Virginia and then across the border to Maryland, colonists scrambled to arms, convinced that they stood on the precipice of doom. Soon some ringleaders appeared, who called on the proprietary government to protect them from the threat, or they

would consider themselves “betrayed to the common enemy.”

Baltimore’s administration managed to survive the crisis by returning colonists’ arms and showing that the reports were false, but the fear remained. As spring turned to summer authorities still refused to admit that James II was no longer king, and new rumors spread “that the Papists had invited the Northern Indians to come down and cutt off the Protestants and that their descent was to be about the latter end of August.”

ARMY MARCHES ON ST. MARY’S CITY

A familiar figure, the Calvert County militia captain John Coode, raised up a substantial force of colonists to march on St. Mary’s City and take over the colony. As they marched on the capital, the proprietor’s defenders gradually defected or faded away. As one inferior officer told his commander, “they were willing to march with him upon any other occasion, but not to fight for the papists against themselves.” This was interesting: “the papists” were not “themselves.”

Clearly, Catholics were outsiders, even if in this case they were the outsiders who had been ruling the colony for its entire history.

By the beginning of August Baltimore’s allies had surrendered to Coode and the Calverts’ experiment was done. As a condition of surrender, the former rulers pledged that “noe papist in this Province” occupy “any Office Military or Civil.” It was a revolution at the top, one that replaced the proprietary elite, many of them Catholic, with a new class of leaders, all Protestant, who had previously exercised power mostly at the county level.

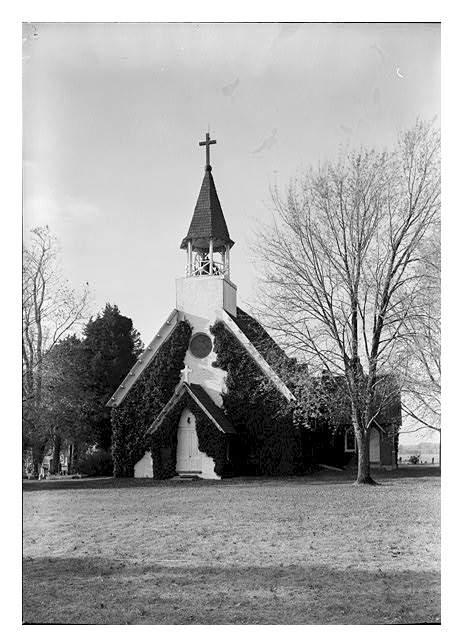

Eighteenth-century Maryland, while still a place with a powerful Catholic minority, would not be a haven of tolerance. The chapel in St. Mary’s City, the symbol of this system, was gone by the early-1700s.

It’s fitting to reflect for a moment on how we got here. The Calverts hoped that they could use the New World to build a society that was impossible in England: a society where Catholics could rule freely and have positions of authority, and where people of all Christian faiths could coexist. That

is not what they got. Instead they found that the animosities and divisions of the Old World followed them to the New, but added some new wrinkles.

The new racial logic that emerged from the stresses of a multiracial society combined with antipopery to create, new virulent fears. These fears, of Catholics and Indians banding together, proved more powerful than the Calverts’ hopes. By the end of the seventeenth century, indeed, these anxieties had spread far beyond Maryland.

They had brought done not one colonial government but three and had changed the face of imperial politics. During the eighteenth century, a new empire came together, one based on the belief that the empire would defend Protestants from Catholic and Indian enemies. It was an empire based on fear and based on a kind of fear that first appeared in Maryland, and proved quite portable. MORE

Discover more from THE CHESAPEAKE TODAY - ALL CRIME, ALL THE TIME

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.